In 1944 – at the height of WWII – Italian POWs arrived in Puget Sound. Their Allied captors allowed many freedoms, including formation of multiple teams in Washington state amateur soccer’s top division.

On the evening of April 17, 1945, players, coaches, sponsors and officials of the Washington State Football Association gathered at Seattle’s stylish Olympic Hotel to celebrate winners of the various competitions held during the preceding six months. During the social hour, guests undoubtedly discussed the latest news of the world, of which there was no shortage. World War II was being waged in two theaters, and while an Allied victory appeared at hand in Europe, President Franklin Roosevelt would not live to see it. Five days earlier Roosevelt had died from a massive stroke, and now the United States had a new leader, commander-in-chief, Harry Truman.

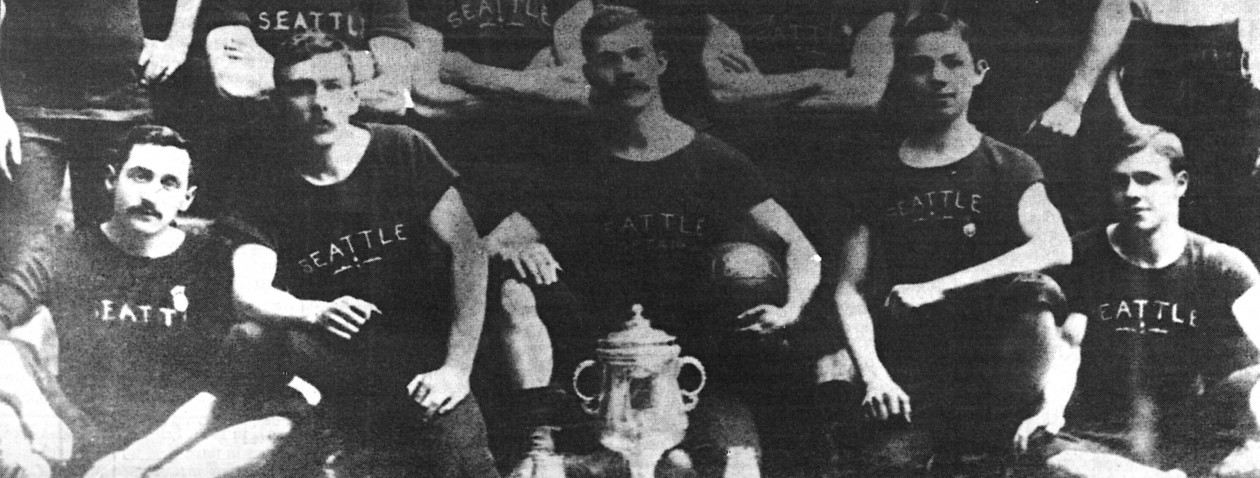

Since the bombing of Pearl Harbor, news of the war had been inescapable. It dominated headlines and everyday dialogue. Now the war was having a profound effect upon the state’s top amateur league, evidenced by the parade to the podium to pick-up the WSFA trophies. A previously non-existent club was being presented three pieces of silverware, including the ancient (1906) McMillan Cup.

At the end of this day, members of this triumphant team would not go home. Instead they would be remanded to their supervising officer and returned to their barracks. Known as the 28th Italian Service Unit, these were officially prisoners of war. Prisoners of a onetime enemy. Prisoners with privileges, yet prisoners just the same.

A World Power (On the Pitch)

Just 10 years earlier, Italian football had announced itself on a much larger stage. Without question, the Azurri were the Team of the Thirties, making a triumphant entrance to World Cup play by not only hosting the tournament but also becoming the first European nation to claim it. From that date until the outbreak of World War II, no national team was more revered than Italy which followed with a gold-medal performance at the 1936 Summer Olympics and another World Cup victory in 1938. During that stretch they ran roughshod, winning 38 and drawing six in 48 full internationals. Such success only served to further fuel a dictator’s desire for a new Roman empire.

Benito Mussolini wanted the Azurri to be the embodiment of his Fascist movement, exhibiting a strength, cunning and physicality reflective of the new, merging Italy. As noted in David Goldblatt’s The Ball Is Round, the national team was exploited, used as a tool to create a warlike spirit. The manager later said, however, that players were generally not interested in their play making a political statement. They loved the game. Soon enough, however, war was a reality.

A Beating on Battlefield

Mussolini joined Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Japan in forming the Axis powers yet was comparatively ill-equipped, undermanned and poorly trained. Many soldiers were unwilling combatants. Consequently, Italy took repeated beatings on the battlefield.

Many of these unenthusiastic conscripts to Mussolini’s army were among the 200,000 taken prisoner by the Allies in May 1943 following the Battle of Tunisia. If being shot at and losing comrades while fighting for a deluded dictator was not sufficiently demoralizing, some Italian prisoners were subjected to torture and starvation under a blazing sun by Tunisian guards. Allied forces eventually divvied up the POWs, and by January 1944 over 50,000 were bound for detention in the United States. Some, however, would soon be given privileges previously unheard-of.

Continue reading Freedom to Play