Forty years on, it remains a remarkable match. Not only did it captivate American soccer’s growing audience of the day and provide a fairytale finish for a global legend, Soccer Bowl ’77 also cast the pathway, for better or worse, for a club and a country seeking to development a professional presence.

For those who witnessed the NASL final between the glamorous New York Cosmos and unfashionable (outside Cascadia) yet fearless Seattle Sounders, it left an indelible mark on the memory. Just a glimpse of the video or photos awakens the senses.

Of course, there was the epic backdrop: a gray, late summer Sunday afternoon, Portland’s Civic Stadium crammed full of 35,548 spectators, some sitting cross-legged on the artificial turf, just a few feet from the field’s boundaries.

There is the ‘Oh, no!’ moment of a partially deaf Sounders keeper being fleeced of the ball for the game’s opening goal. There is the rapid reply of Seattle to equalize, the relentless pressure and the sheer openness–rarely found in a final–that leads to dozens of chances (22 shots on target, two others by Seattle off the frame itself). And there is the chaotic scene at the final whistle, the crowd streaming onto the pitch and the shirtless Pelé running and hugging his teammates.

Simply Unforgettable

Such a day is impossible to forget. August 28, 1977 is a date holding significance to sporting historians. Earlier this summer a journalist and film crew from Italy preparing projects to mark the 40th anniversary stopped in Seattle. Among those they interviewed was Jimmy McAlister, then a 20-year-old homegrown rookie and postgame recipient of Pelé’s green jersey.

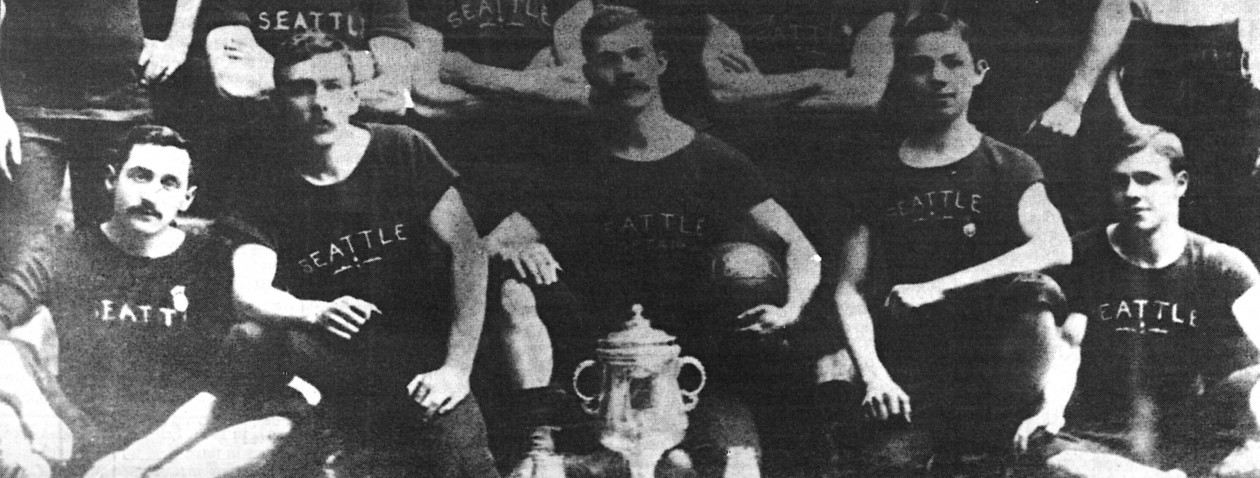

For those who played in the match, particularly those who represented Seattle, they don’t require media to validate its importance. Locals like McAlister and Vancouver’s Tony Chursky were living the dream; they had grown-up never even fantasizing such a scenario. Most of the Sounders were Britons. Some had first-division pedigree, others were plucked from England’s third and fourth tiers. The captain, Adrian Webster, whose odyssey included a semipro stint in Vancouver, recently wrote a book about it.

For those who played in the match, particularly those who represented Seattle, they don’t require media to validate its importance. Locals like McAlister and Vancouver’s Tony Chursky were living the dream; they had grown-up never even fantasizing such a scenario. Most of the Sounders were Britons. Some had first-division pedigree, others were plucked from England’s third and fourth tiers. The captain, Adrian Webster, whose odyssey included a semipro stint in Vancouver, recently wrote a book about it.

Then there are those who watched the drama unfold. Some were lucky enough to buy one of 8,000 tickets allotted to Sounders fans the morning after ousting LA in the semifinals. At least that many worked the secondary market. All in all, at least half of the record throng was firmly behind Seattle. The rest of the 56,000 who attended that semi were glued to our TVs, watching the syndicated broadcast on Channel 7.

No Regrets

While emotionally draining, Sounders players and fans alike have long taken solace in the fact that our boys fought the good fight. They never backed down. After winning seven straight they were deserving finalists and believed the championship was within reach.

The Cosmos were arriving in Oregon having scored 19 times in five playoff games; Giorgio Chinaglia remains the most ruthless finisher ever to roam this continent. These were Galácticos decades before Real Madrid coined the phrase. Carlos Alberto was a World Cup-winning captain, Franz Beckenbauer a two-time (and reigning) Ballon d’Or winner. Although 36, Pelé remained a formidable force. The majority of neutrals believed the Black Pearl was fated to go out a winner.

The Cosmos were arriving in Oregon having scored 19 times in five playoff games; Giorgio Chinaglia remains the most ruthless finisher ever to roam this continent. These were Galácticos decades before Real Madrid coined the phrase. Carlos Alberto was a World Cup-winning captain, Franz Beckenbauer a two-time (and reigning) Ballon d’Or winner. Although 36, Pelé remained a formidable force. The majority of neutrals believed the Black Pearl was fated to go out a winner.

“It would be great for Pelé if he finished off his career with a victory,” quipped Seattle coach Jimmy Gabriel on the eve of Soccer Bowl, “but I’m afraid he’s going to be very sad.”

Banking on his team’s supreme fitness and commitment to one another, Gabriel asked his players to incessantly swarm the Cosmos. “Jimmy said (the Cosmos) are better at the continental, South American-style slow build-up, but we’re not going to get into that kind of game,” says David Gillett, Sounders centerback. “We’re going to unsettle on the ball from the very beginning.”

“Paul Gardner, the TV commentator, didn’t think we could keep up that pace. (But) we were a pretty fit team,” added Gillett. “We wanted to make it a good final and leave it all on the field, and we had taken control of the game.”

Exponentially Out-Spent

Warner Communications may have spent exponentially more on creating a contender (Pelé alone made $1.4M–near 10 times the Sounders starters, combined), but Seattle countered with a collective ethos of All for One. “It was all about the camaraderie of the players,” claims Webster.

Many Boomer fans will confirm that today’s Sounders FC success at the gate–MLS attendance records, regularly drawing beyond 40,000–is directly tied to the community’s ties to those original Sounders, who pulled over 25,000 themselves.

Yet many a successful team has come out of Puget Sound since Soccer Bowl ’77, and most of them were also underdogs exhibiting those Gabriel tactics: high pressure, playing in sync. And they have been mostly homegrown sides, following in the footsteps of McAlister (his son Bobby starred for Seattle University 2004 NCAA Division II champions).

Living Proof

You can even trace a narrative of unfinished business in 1977 and culminating with the MLS Cup triumph in Toronto 39 years later. Both Webster and Gillett see Sounders FC coach Brian Schmetzer as a manager rooted in the tenets of Gabriel (Schmetzer’s assistant and mentor in Seattle’s A-League era).

“Brian came from that system, where it’s not about 1-2 individuals,” notes Webster. “It’s a good foundation.”

“Brian came from that system, where it’s not about 1-2 individuals,” notes Webster. “It’s a good foundation.”

“There’s a balance there,” he adds. “Now they have the academy in place, and hopefully you get the young American players continuing to come through. The young players need to know there’s a pathway to the first team. Brian, being a local boy, will give them opportunities and push them through.”

Three years after Soccer Bowl ’77, a 20-year-old Tacoman, Mark Peterson, was not only starting, but scoring 14 goals up front. A year later, he was joined by another Tacoma product, Jeff Stock, in the XI, and Schmetzer was signed by Alan Hinton. The Sounders reserve team program, the first of its kind, initiated by John Best, was regularly bearing fruit.

Players such as McAlister, Stock, Peterson, Schmetzer and Chance Fry mentored the next class and coached successive waves; Jordy Morris spent his early days playing in Fry’s Eastside FC.

A Sustainable, Steadfast Commitment

While Seattle was committing to a sustainable formula of developing homegrowns and supplementing with quality players committed to an earnest work ethic, most of the NASL was smitten with the Cosmos way. Owners saw huge crowds at Giants Stadium and the first of multiple championships as a sign that clubs could buy championships.

Gillett was fearful a Cosmos victory would result in such a misguided approach to growing the game. Six expansion teams flooded the NASL the following year, and many teams sought to recruit high-priced (and mostly overaged) players to compete with the Cosmos.

“I was really disappointed when we got beat, because when you see what happened later, all the teams emulated the winning team; they all tried buying a team and spent too much on players,” said Gillett.

The Road to Ruin

In 1982, New York won a fourth championship in six years (again defeating Seattle). However, the onetime 24-team NASL was hemorrhaging money; by 1983 only 12 franchises remained, and a year later the whole league was kaput.

Today’s single-entity structure in MLS is a living reminder that the Cosmos way, while glamorous and seductive, is also the road to ruin in a sport struggling to gain a foothold.

“If we had won, that would’ve sent the message that you don’t have to spend all kinds of money, if you have a team that plays well together and likes each other, if you do all the right things–you can be successful without going bust,” laments Gillett.

“That’s what came out of the Cosmos winning and that was why I was more disappointed,” he says. “More people picked up on the fact that you can buy a winning team. That turned out to be a disaster. Had we won with a workmanlike team that had some talent, it would’ve sent a whole different message.”

A century ago, Robert Frost wrote of The Road Not Taken. Seattle diverged from the pack and, as Frost contended, “that has made all the difference.”