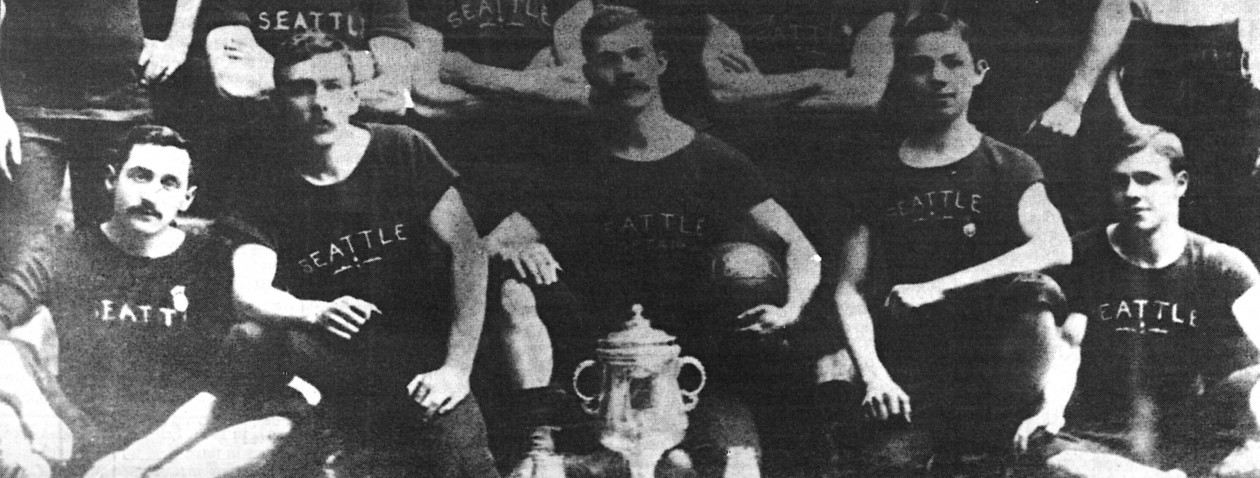

It all began as a working vacation for David Gillett. In 1974, the 23-year-old Scotsman first stepped foot in Seattle, where pro soccer had never existed. He was coming to play central defense, but Gillett was soon all-in as a missionary for this emerging sport, conducting clinics and making plentiful promotional appearances.

Back in Britain, where he played for Crewe Alexandra, the job was pretty much two hours of daily training, with a match or two each week.

It had been much the same for Adrian Webster when playing for his hometown club of Colchester, in England. He moved to Vancouver to play semi-pro and then heard about the NASL coming both there and Seattle soon after.

“I was very fortunate that it was the Sounders and John Best and Jimmy Gabriel that I played under,” Webster offers. “Not all of the clubs in the NASL were run as professionally.” Soon Webster was starting on the backline with Gillett, and the city adored their new team and their tradition of applauding the fans each night from the center circle.

Webster has kept virtually every contract he signed as a player, beginning with his first, for $700 a month plus an apartment for his family.

All-Inclusive Deal

Gillett earned $800 per month, plus a car and a shared apartment on the Seattle Pacific University campus. All, told, it would be $17,000 in cash today, for a 20-match season, before returning to England. It bumped up 25 percent in 1975, and after being signed to a 12-month deal (clinics and appearances in offseason) and named honorable mention all-NASL his new contract was $33,000 by 1977.

In addition, Gillett got a $10,000 annual endorsement deal with Nike. His agent, former Sonics executive Bob Walsh, was also representing Seahawks stars Jim Zorn and Steve Largent and, thus, well-connected.

“It was a no-brainer move,” he explains of his decision to move his year-round residence to America. “John and Jimmy made it enjoyable.” Gillett also shared that not only was NASL pay comparable to England, some of the biggest British stars actually made more in the U.S.

Down the road in Tacoma, in 1976, the ASL Tides were operating on a different scale. Crowds at Cheney Stadium were a fraction of those in the Kingdome. If the cancelled check of goalkeeper Bruce Arena is any indication, a squad player was grossing under $4000 ($18,600 today) for a five-month season. No doubt their dream was to reach the relative riches of the NASL.

In 1979, the Sounders traded popular goalkeeper Tony Chursky in retaliation, many believe, for his activities as a players’ union representative. Webster, the team captain, succeeded him in that role and was a central figure in the Sounders players joining other clubs in a one-week strike. At the end of that season he was released and soon found work in the emerging Major Indoor Soccer League, for $10,000 over four months, with Pittsburgh.

Sounders Go Year-Round

Alan Hudson was one of several Sounders to spend the NASL offseason in MISL, but by 1980 Seattle was playing year-round, 32 games of 11v11 and 18 games of 6v6. Consequently, the offseason was reduced from five months to one, October. At the end of Hudson’s four seasons in Seattle published reports pegged his annual salary at $100,000, the highest known figure of the Sounders’ NASL era.

Hudson wore Nike boots, but his endorsement deal was cashless. Instead, he was treated to an all-expenses-paid loyalty trip to Hawaii. He described it as, “Absolutely magic,” adding, “I was more than happy with what I earned because I loved playing in Seattle.”

Big Fringe Benefit

Beyond pay, one of the lasting benefits for foreign-born players was, and remains, access to green cards, or permanent U.S. residency. To this day, a green card is greatly beneficial, for both club and player. MLS clubs have limitations on international roster slots and obtaining a green card for one player enables the team to seek another international. Not surprisingly, clubs hire immigration attorneys who specialize in expediting the green card process.

For the player, it opens a pathway to life after soccer, or at least after their playing days. If not for green cards, many of the Sounders and Stars players who remained may not have been around Puget Sound to help foster the growth of the game and development of young players.

Webster began his coaching career, in Arizona, by 1981. Gillett served as GM for FC Seattle, which developed and played local men and women almost exclusively. When he left Britain, he was looking for more than just a life in soccer, and it has been.

For the past 30 years his connection to the game is mostly as a fan. Longtime Sounders fans still recognize him. Michelle Akers idolized his game and wore his number. Gillett’s felt embraced by the community from the day he stepped off that plane. He wasn’t coming to get rich and, few people have grown their fortune by working in the game.

Gillett, having seen soccer business from both the player and management side, sometimes summarizes it with a little riddle. “You know how a multi-millionaire becomes a millionaire?” he asks with a twinkle. The answer: “He buys a soccer team.”

Thanks for reading along. If you enjoyed this content, perhaps you will consider supporting initiatives to bring more of our state’s soccer history to life by donating to Washington State Legends of Soccer, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to celebrating Washington’s soccer past and preserving its future.